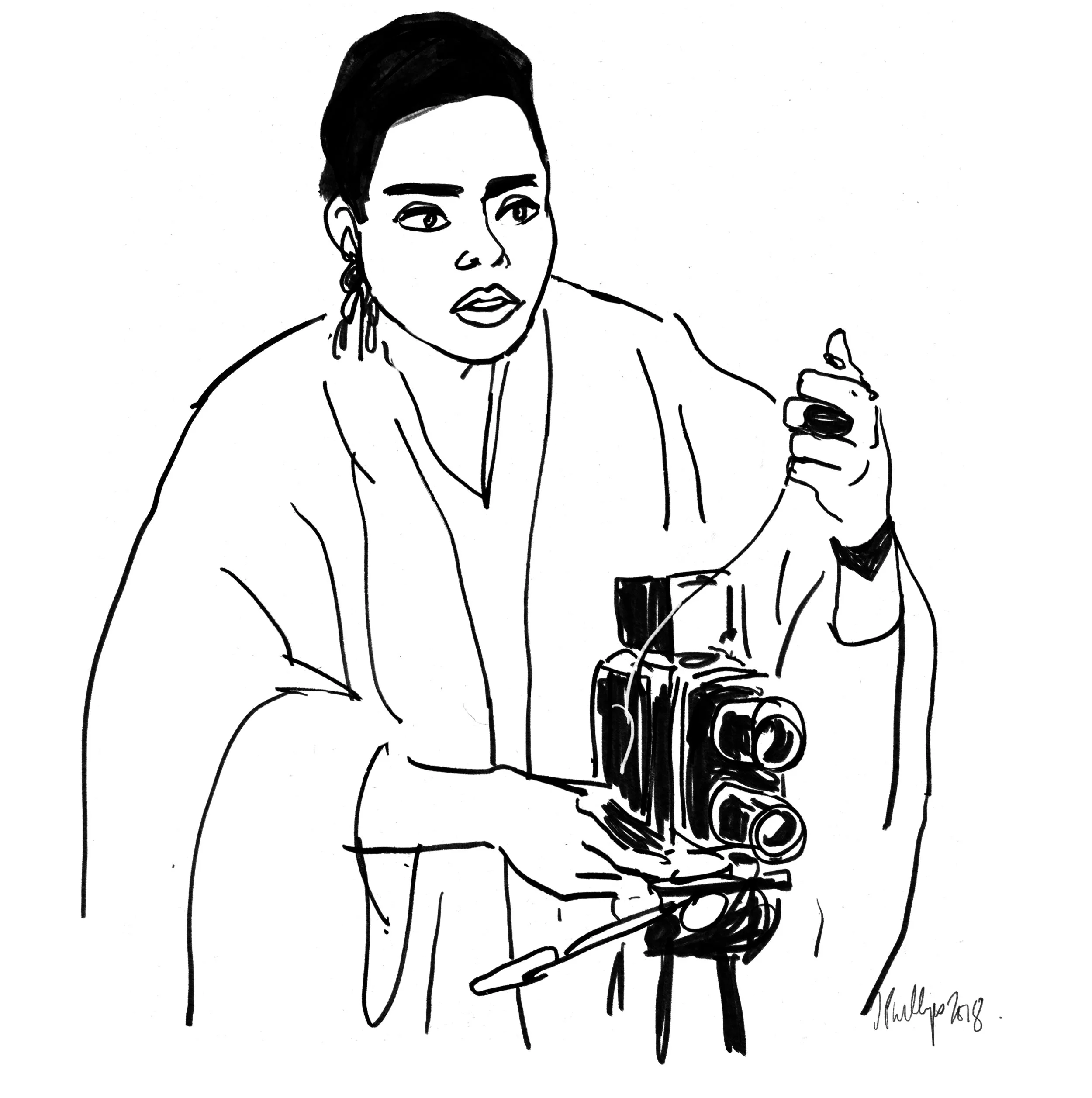

Cheryl Dunn, Filmmaker and Photographer

Cheryl Dunn is an American documentary filmmaker and photographer.

Dunn has published three photobooks—Bicycle Gangs of New York, Some Kinda Vocation, and Festivals are Good. Her award-winning documentary film Everybody Street (2013) tells the stories of New York City’s most iconic street photographers. She also has shot commercial campaigns for clients like Nike, Adidas, and Quicksilver.

Cheryl talks to us about photo books that inspired her photography and what she learned making Everybody Street.

Subway,

by Bruce Davidson

“I grew up in North New Jersey. I was close to a giant city but wasn’t in it. What you knew of it came from the news, so every time we would go to the city to concerts or Yankees games, our breath would be taken away because it was so dangerous. It was thrilling. Seeing this book reminded me of those real life emotions that I had with the people and environments. It brought me emotionally and physically back to a time in my childhood.

I admire Bruce’s commitment to his projects because they were self-motivated; it completely came from within. I ride a bike often, so sometimes things fly by my vision and I'm like, "Oh shit, I should've taken that.” I think of Bruce and him saying, “Stop, go back, and try to get the shot. Don’t be lazy. That’s what you’re here to do.”

Street Cops,

by Jill Freedman

“She became a good friend of mine after doing the film, Everybody Street. I’m inspired because she was a woman doing these assignments. She was thorough, extensive, and made sacrifices. The whole dynamic of her inspiration to want to do it in the 70’s when there were a lot of Serpico’s and these stories and films about corrupt cops. Her motivation was to humanize policemen, to show what the job was. I don't think a man could've done what she did. You see this being pretty macho. It was very dangerous. People burned out. The city was bankrupt—very gnarly circumstances and lots of crime. She really showed this sensitive human side to the cops—it was funny, humorous, and intimate. These pictures reflect her energy and personality.

Sometimes, you get a feeling of energy from great art that emanates from the painting or the photo. Sometimes, you don't understand why, you just feel it. Sometimes you learn more about that, and you go, "Oh now I know why." Because that artist puts so much into making that work and it emanates that, I believe. When I got to know her, learned more about that body of work and the process of years she did that, that was all confirmed for me.”

Photographs,

by Fred Herzog

“I learned about Fred Herzog’s work about a year after I made Everybody Street. He’s such an incredible colorist. The cover of this book is just one of my favorite pictures. He's hailing a cab. He's got like an H-Bandage on his hand and a cigarette, like he's just shaved and got tissues on his face. You can tell he was committed to walking the streets. I think that he just did it and did it and did it, really ... I don't know much about Vancouver so it kind of shows an era to me, a certain light that seems to be specific to this landscape. His compositions with objects, odd desolation, and a certain period of time is a gritty elegance that is profound. I just love this book. I love the size of it. I love that it’s a little square book. You know what a book is, it's physical, like a precious object. That's what this book is.”

A Tale of Two Cities,

by Meryl Meisler

“Meryl was a teacher in Bushwick during the disco era. She would teach and then she would walk around the streets in Bushwick. There were a lot of riots happening and it was pretty beat up. She’s another example of having a day job—as a teacher—and doing photography for fun. Then she did this out of curiosity and love for her community and her kids—how her sympathetic eye and her love and wonderment of the characters and of this neighborhood, of this area of Brooklyn.

It's a great example of why New York City is filled with great photography. The history of it is so amazing, like Rebecca Lepkoff’s work and the Photo League, when people basically lived on the streets. This thing about privacy and public is kind of skewed. There's this sensibility of New Yorkers, an openness. They're all these extremes. In her work, you see kids playing in kiddie pools, people living their lives on the street, lawn chairs outside an apartment because it’s too hot inside the apartment. This era of New York was really endearing. ”

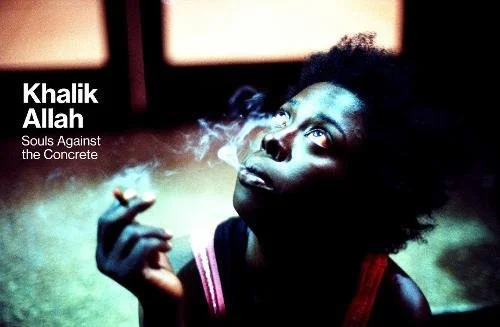

Souls Against the Concrete,

by Khalik Allah

“This book is really beautiful. He also made a really profound film. He talks about how you start out in a certain way, and then you find your voice. I think he started with black and white. He was a printer. He would go to this certain block and street in Harlem and was committed to documenting this particular street corner and the people. He was very diligent in doing this. He's very personable and generous and amazing, and he was let in. Even though the people there are doing drugs, they opened up to him. He spent many years going to this particular area and knowing the people. These pictures are made with available light, super wide open with like a 1.2 lens. There's a shallow depth, the colors are super—it's so cinematic.

It's like you look at these pictures and you're pulled into this person's heart. They're so emotional. Because of the shallowness of the depth of field, it kind of conveys that someone had quite a difficult life and needs hard skin to survive, but somehow the skin is reduced to a thinness. You kind of see into this person. I guess that's maybe why it's called "souls against the concrete," you really see the subject's soul. It definitely has to do with Khalik as a person taking the picture, but the way he is shooting it's like as if that soul is completely revealed.”

Cheryl, what is something in your industry that deserves more attention?

I think there's the short attention span, which is due to Instagram, and then there's the in-depth attention which is retrospective. I think people are interested in photography more than ever before because it's easy to be a participant. It's not something that other people do which lots of people can't do. I always think that what needs more attention is the art of editing.

They don't pay enough attention to it in school. Yeah, you can bang out a thousand million cool pictures, but do you care for those pictures? Do you archive those pictures? Do you nurture those pictures? Can you narrow them down to size to say what you want them to say? Can you pick one? That takes a long time.

We live in a much faster world now. I don't think that's necessarily beneficial to art-making and film making. Depth can be lost. I think recognizing the value of that depth and celebrating that it is something that is important to remember.

I made my last book thinking, “Let me quickly put this book in the world because I want to dive into making a feature film. I'm going to have to be off the grid for a while. Here's this body of work, here's this festival that I made that I had been shooting since like ‘94. I'm going to bang that out." It actually took me fucking forever.

You know, after you take 15 or 20 years of stuff and decide on 150 images, it’s hard. It takes time. There's reasons why something is juxtaposed next to something. It's a conversation. It's something that takes you on a journey. That's not an easy edit or easy to do.

You know when people ask you to turn a shoot over in like a matter of hours, if you're shooting for something that's newsy and it has to be out the next morning? People usually say okay. If someone asked me for an edit and gave me one day, I'm going to give you a pretty broad edit because it takes a long time. I’ll take out the mistakes and bad focused shots. And they’re okay with it. This person understood that that's what they do. Because sometimes people on the other end don't understand what that is.

Everybody's Street is a gift to many visual storytellers. How did that project change you?

It was kind of like going to grad school. Although I have never gone to grad school, I would assume it was like that because I learned so much. Also, being able to spend a day with a master in the field that you admire— being able to ask them anything you want to—was such a gift for me.

The post-production was emotional. I felt like it's one thing to make a film, a story you wrote or something that's not real, but then to make something with that many artists and people with 60-year-careers and the responsibility to portray them in a certain way.

I also knew I wanted to share that work with a new photographic audience, not really knowing whether a 20-year-old would find this film engaging. I definitely received some criticism from producers in the post-production phase, saying, "You should have some younger photographers in there."

I did interview some younger people that could speak more to a generation as a whole. I realized I had time to talk to a 20 or 30 year old, I don't have time to talk to an 89 year old. So that film is going to have to wait. This is the film I'm making. This is what I want to impart on an audience.

I thought about how to contrast a 96-year-old Rebecca Lepkoff and translate her work to make her come across as punk rock as she is to a 20-something audience. Jill Greenberg was there in her leather vest that she's probably had since 1975, looking super style-y and awesome and punk. These young girls were coming up to her completely fan-girling out on her. They knew her because they saw my film. That made me really happy. The attention that she got was invigorating to her as well. So that's what it's all about, I think.

We were wondering if there were any moments where you struggled to tell the story that you had in mind, and if so, what you did to overcome that?

Oh god, all the time. I guess when you think about shit you're going to do and it's big, it's a lot of pressure, and you can kind of crumble. If you just get your ass in the chair and put in the time—I pecked away at this—then that's all you can do.

You have to get in the zone and try to calm those distractions—a film is like building a house. A film can take years. It takes other people, but if you're the only one building the house, it'll take you a long time. I try to—and I'm not really good at it—being hard on myself. I feel like being hypercritical and hard on myself actually gets me to make stuff.

Sometimes my process is good. I know when I made Everybody's Street, that was my first big feature. I had no idea what it would entail. Then you finish that and you're like, holy shit, I'm never doing that again. It's in the world and you’re amazed.

I just went to Russia, and there's a line of teenage kids that came to show me their pictures because my film really inspired them. You realize all the pain and sacrifice is worth it because you might've changed somebody's life. A couple of years go by and then you're like, I'm going to do another film. But you know the process, so you get through it. You just got to get in the chair and think about the day.

Sometimes you can't find inspiration, it's kind of magic in a way. It's there, then it's not, but if you're not in the chair, you're not inviting it. If you're not in the chair, you're not near the keys, you're not looking at the thing, then you're not making it. So you've got to sit down, get in there and start.

Do you have any advice for a visual artist about their role in society and the impact that their work can have?

Visual artists can take it for granted that you have an insight to share. Until you're around other people that don't do that, you realize there's something that is different about the way you see the world, the way that you conduct yourself or what you can impart in the world.

I always think that if you have access to a world that maybe might be inaccessible or you find yourself in a circumstance to tell a story that most people can’t, it's sort of an obligation to tell that story.

My studio is a block from the World Trade Center. I had basically an all-access pass to what the hell was going on down there. It was dangerous. They just wanted the economy to keep chugging along, so they opened up the shops. Meanwhile, glass is flying out of the buildings and gas pipes are exploding underground. They opened the streets five minutes later. It was dangerous. As you can tell, half of those brave first responders are dead.

I saw what was going on and you couldn't get here unless you had your driver's license that said you lived here. I realized this was my unfortunate obligation—fortunate and unfortunate—but this is my obligation to share what I have access to.

Street photography has no agenda, it’s a portrayal of the way people live and what's going on with the least amount of acting. A street photographer doesn’t believe in rules. The practice is you go out there to document what you’re seeing, eyes wide open, witnessing what is unfolding before your eyes.

To me, that's the purest portrayal of what is happening. I think that's a very, very important practice. It's an important thing to live in, to be a citizen journalist. You know, every documentarian obviously has a point of view, but I think street photography is the most balanced point of view that you can share with other people.

I post things or point of views that I don't agree with. But it's what I saw on the streets, the protestors at the Democratic Convention or the Republican or whatever. This is what my camera has seen, this is what I saw at this moment unaltered. This happened.

If that's your world, if you're in the middle of it, you have this first hand access or experience, I think it's very important to take advantage of that because that's unique and specific to you. As an artist, you're always asking, “What's unique about what I make, my voice, what I see, what I create?"

In your world, and in you, is a world that is not like anyone else. You have to recognize that when it confronts you and go with it.

Can you describe a photographic memory of a moment that changed things for you?

I usually remember the pictures that I don't take, for whatever reason I chickened out. I couldn't pull the plug. Those are ingrained in my brain. The ones I take I'm like, I got it. I captured it.

Sometimes I just choke when I'm around people that I revere and think are such great artists. Two times, actually, I was in the belly of Giants’ Stadium. It was a show called "Field Day,” a three-day camping festival. The town that it was supposed to be in pulled the permit like three days out.

They had to relocate the show—it was like Radiohead, Beastie Boys, etc. They put it in the Giants’ Stadium, which is just like a cement police state basically; it was terrible. I found myself wandering in the stadium.

I suddenly was in a hallway by myself with the Beastie Boys, like they were walking right at me, only them. You can shoot segments all the time. I exploded. I had four fucking cameras around my neck and I just quivered and froze and didn't take a picture.

Then another time I was at All Tomorrow's Parties which is up at the Catskills, washed out, in this weird old Borscht belt hotel thing. Jim Jarmusch, who was the festival’s curator, and Sara Driver were in a field at dusk by themselves just coming out of somewhere and it was the best fucking picture—and I didn't take it. It was a private moment and I didn't want to be a dick, but it would've been iconic.