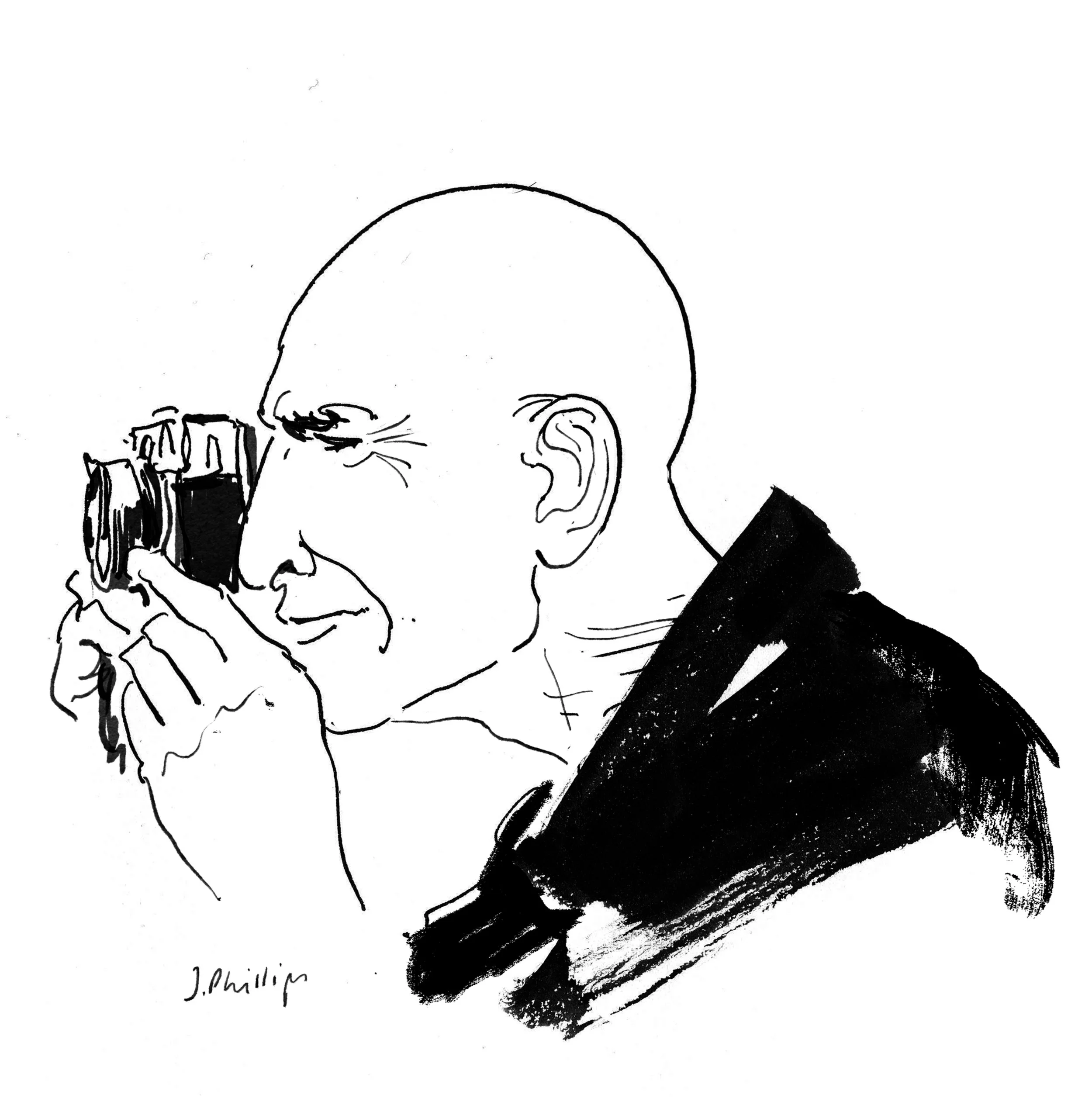

Danny Clinch, Photographer

Danny Clinch is an accomplished photographer and film director who has shot and filmed a wide range of artists, from Johnny Cash to Tupac Shakur, from Bjork to Bruce Springsteen.

His work has appeared on hundreds of album covers and in publications like Vanity Fair, Spin, Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire, and more. He has published four books, most recently Still Moving, and has had his work featured in numerous galleries.

Danny shares three photo books that inspire him, along with some insight into what goes into creating iconic album covers.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.

Passage,

by Irving Penn

“Irving Penn is a major influence on my work. I am amazed by his ability to handle any assignment. Still life, portraiture, fashion, and personal work are all handled with an amazing eye and seemingly simple concepts. His Worlds in a Small Room series and his natural north light portraits inspired me to begin my own natural light series of musicians for the last 23 years, beginning in 1996 when the Beastie Boys put on the Tibetan Freedom Concerts. This book, Passage, is a beautiful retrospective of his career which gives the reader insight into the diversity of his work.”

Bike Riders,

by Danny Lyon

“Documentary photography and a pure insider look at greaser biker gang culture was my dream land growing up. This book was my introduction to Danny Lyons work and I couldn't get enough.

As we learned, he infiltrated the gang without their knowledge and risked his life by publishing the work. This led me to Conversations With The Dead, Knave of Hearts and many other books of his. He introduced me to the 665 Polaroid format, and I have had a love affair with Polaroid ever since.

I also discovered his documentary films and these films, along with the films and photography of Robert Frank, inspired me to make my own documentary films. They have informed my film making style.”

Films,

by William Klein

“William Klein does it all. Photography, film, graphic design, fashion, and street photography. There is no end and he just seems to get up and create all the time. There is a madness to his work and it makes me want to be right in the middle of it. This book shows me that there are no rules. Make your own rules, then break them. Get up and make shit! This book gives you an idea of the breadth of Kleins work. It inspired me to stretch out into other creative areas myself.”

Danny, your most recent book Still Moving is a beautiful collection of intimate portraits of some of the most important musicians of the past decades. In creating this collection, did you learn anything about your work that you hadn't realized or noticed before?

I think it just made me realize just how deep my archive actually is. I have a camera with me at all times, whether I'm walking down the street or whether I'm going to a show, or I'm at a family gathering, I always have my camera.

What is your process in terms of keeping your archives properly organized?

Well, I started back in the day when we were shooting film. Contact sheets and all that. I still do that to this day, but I shoot a significant amount of digital as well. So I started a system back in the day, fortunately, because I know there are some people that are pretty unorganized in that respect. Every job has a job number. Everything is documented. That job number is on the back of every contact sheet and on the side of every roll of film. I've recently started the process of digitally archiving my film and re-housing everything. My stuff has all been archival, but we're just re-housing it into newer envelopes and storage containers.

Is your current system the same as when you started or have you tweaked it over the years?

Yes, well now it's digital so there's a change there. We now have spreadsheets instead of a case history. We used to have one of those little red books that my wife started way back in the day. We just would call it case history, and we'd just start with number one, and we just keep adding to it.

It's only changed in the sense that anyone would change it to keep up with technology. It's still just a fairly simple organizational idea.

When you need to trace back a certain shoot, let's say someone wants a print or a publisher wants to see a certain thing, how long does it take you to find it? Let's say that it's from the film days.

It shouldn't take that long. I have a storage unit near my home in New Jersey, so sometimes really old stuff is in there. But a lot of the really important negatives and the things that we use on a regular basis are either right at our fingertips or they are already scanned, and there's a digital file that we can make a print from. With my fine art prints, I'm doing a lot of digital archival printing, versus silver gelatin.

How did you make the decision to move towards digital archival printing?

I think the control that you have in the digital world is really appealing, and the fact that I can do it right in my studio. I have my own personal printer that works with me and we’ve develop a language together that is really consistent. I don't have to explain it to her over and over again, especially when we get to certain prints. We just have a profile there, and it's very simple. It's beautiful and just as archival as the others.

You mention that you always have a camera on you. Is there a particular camera that's always your go-to to carry around?

Yeah. I have the Leica M10. I have a Leica M6 and a M4-P. Oftentimes I will roll out with one film Leica and one digital Leica, and then I have the opportunity to shoot either or. Their lenses are interchangeable and I love rolling that way. That's my favorite.

You just have them both hanging on your chest basically?

Yep

When you have a dedicated shoot do you move away from these Leica usually? You had mention that the cover for the Still Moving book, a beautiful photo of Eddie Vedder, was shot with Canon 5D Mark III.

When I show up to a shoot like that, that photograph there, I shot it on film. I shot it on digital. I shot it on Polaroid. I have two really beautiful Polaroid frames from that same moment. So I bring with me an entire bag of cameras. A Hasselblad, my 5D, I have the half-frame cameras, the Diana, the Holga. I have a Widelux, and then I have my Leicas. So I like to give myself options.

When I’m creating a package for someone, I really like to mix the document with artfulness, you know?

That's a lot of cameras! What is the process like having that many options? Is it that you might spot a particular moment, like in that case with Eddie, that gets you excited and then you run it through all or most of the cameras on hand?

I run it through the cameras that I think are suitable. When I'm shooting these days, and I'm on an assignment like that shooting my 5D, and I'm rocking and rolling I might get into a really beautiful spot that I feel will make for a great portrait. And all I have to do is grab my Hasselblad or grab my Leica. I'll set it up digitally so I can see what I'm doing, what the light looks like and I can feel the composition, and then I'll throw some film at it. That's when it really sort of comes together most of the time.

So in this case the digital shot ended up as the cover of the book. Did the film shots of that particular moment end up anywhere?

The Polaroid versions ended up on the cover of a couple of the singles. Because I do like this Polaroid thing. I purposely am not really white glove about the Polaroids when I pull them. Some people treat them with kid gloves. I don't, on purpose, because getting some dirt and some grime and maybe even a little bit of solarization in the shadows, I think just gives it character. I know that I already have the positive. So I have a lot of options I'm giving myself. So it's really cool to let some of those happy accidents happen.

There's a really cool shot of Eddie that I shot with my Konica Instant Press camera, which is a Polaroid camera from the '70's. He took the ukulele and just threw it over his shoulder and he's looking at the camera in that one. Sometimes I'll pull them early and hold them up to the sun and let a little bit of the shadow detail kind of bleed through and get a little solarized. So I enjoy doing that as well.

So a bunch of those cameras that you just mentioned are from various different eras. How would you say your personal aesthetic and style has developed over the years, as you yourself moved through some of those eras?

You know, I'm a big fan of the document, you know, the photograph as a document, documentary films and that. I've always felt like I want to balance the document with some really artful stuff. I was always interested in motion and pulling way back and getting the atmosphere and the location that you were in. I was never really so much a long lens type person, because I like to just sort be in the middle of things. And you know, using the Holga and the Diana and the Widelux, and slowing down the shutter speeds, double exposures, taking chances with them. It opens up the door for some happy accidents and some really artful stuff that, when you're doing like an album packaging or editorial piece or something, creates options for the person who is laying out the project.

Back in the early 90’s when I was shooting my early Indie Rock and Hip Hop work, cross-processing film was popular. I was in on that myself. I look back on it and it certainly is very trendy and very cool in a certain way, but I’ve always loved classic photography, the stuff that never went out of style. When you look at Richard Avedon, or Irving Penn and Annie Leibovitz, and stuff like that will never go out of style. It's just so classic. There's no real gimmick involved, you know other than great lighting and a great eye.

I think for me, going back into that work, I've often re-scanned negatives and changed the look by taking out the high-contrast and fully-saturated color the cross-processing created. Some shots I would never change, because that's what they are, they're classic in that way and that's where they should be, and that's why we shot them, and how we shot them. But there are other ones where like, I like kind of sucking out some of that trendiness, you know?

It does become very of that moment in a sense.

It does, and I'm happy to have been in that moment. There's a lot of great imagery that came out of it, when you think of the people of the time, Michael Lavine and Frank Ockenfels, who I really admire. That sort of thing.

Was there ever a moment where you got a new camera that ended up changing your style?

The Leica. I got my first Leica in like, say '94 or '95.

And how did it change the way you shot?

It's just a very intuitive camera and it allows you to disappear, I think, more than most cameras. In the circles that I run in often, it's musicians and it's like relaxed, and I see people come in with a huge lens with a huge camera, like a big Canon 5D and a big zoom lens on there, and to me, it's a vibe killer.

Unless somebody says to me, "We're hiring you to do this backstage moment, and we're expecting a lot from it." Then I'll bring my 5D and my primes and zoom lenses. It's a great camera, because I think the images you get from the camera on the digital side of things are really awesome.

But you know, to be backstage and to roll with just M10 and a 35mm lens. If I have that, I can get whatever I really need at the end of the day.

Are there situations where they want it to be film, and you have to bring the M6 instead of the M10?

Yea. In fact, I'm going to shoot something this weekend and part of it involves shooting stills on a film set of concert film/documentary. They want me to shoot film because they like the classic nature of my work in that zone. They also are interested in using contact sheets with the grease pencil marks and stuff.

When you are shooting portraits of a fellow creative, like the musicians, what are some things that you do to influence the energy of the environment while you're shooting?

I love to be able to play music in those situations. If you have a great playlist that you know that person's going to respond to, you literally can be prepared when you know a great song is going to come on. You can see their expression and their body language change. Someone might just start dancing or grooving, or even a little sort of change in the energy.

I've had a couple of times where I've put together some really awesome playlists and I can't even take credit for the ones that my good friend Gary Ashley made, who used to work with me for many years. We would talk about who the artist was and he'd put a playlist together. On more than one occasion, one time with Bruce Springsteen and another time with Ringo Starr, they both stopped in the middle of the shoot and said, "Okay, who made this play list? I got to get this playlist. Can I have this playlist?"

It was often early rock and roll, along with new fresh music that people may not have heard. Classics that they love. I was doing a shoot with Elvis Costello and we had some great music on, early rock and roll and he asked if I knew about Lee Dorsey, which I didn’t. So he goes, "Well, you got to check out Lee Dorsey." I always play Lee Dorsey on my sets now, and I always play James Brown. James Brown is one of my go-to artists. Everybody's mood can change when you throw a James Brown playlist on.

Aside from playing music, any other ways to impact the atmosphere?

The other thing with musicians is, you put an instrument in their hand and their whole body language changes. Their shoulders relax and they get distracted. Honestly, the best images come when they're distracted, because it's a real moment, you know?

So you bring the instrument?

No, but I invite them to bring theirs.

Gotcha. Okay.

I just did all the stuff for the Bruce Springsteen’s Western Stars record and I made sure that he brought a couple of guitars with him. He brought these beautiful guitars and then when you're shooting details like someone's hand the background of it is a beautiful old Gibson. With Eddie Vedder, for example, putting a ukulele in his hand, or putting a guitar in his hand, it just gives them their little comfort zone.

Not all musicians, are signed up to be doing photo shoots all the time, you know? They're like, "I don't like having my photo taken. You can take my photo when I'm playing, but if I have to sit there and be directed ..." It's not often their favorite thing to do, which is why relationships are so important and why I have repeat customers and friendships with people, over the years, because I just try to keep it as relaxed, and real, and honest, as possible.

You mention the close-up of the hand with the guitar in the background. When you do these kinds of shoots and you're making a package for Bruce for a new project, how do you split what you're doing between wider shots and the detail shots? Do you start with one kind and then go to the next? Is there a certain order for you?

I basically do a little bit of both in every situation. So, I'm thinking in my head. I’m thinking a simple, beautiful, elegant, honest portrait. Portrait, portrait, then publicity, publicity, and now you have to think social media. You have to think all these other things. You have to think vertical, horizontal. You want to cover off on those things. And then I'm like, okay, now take some chances.

So first you check the boxes of what the client wants and then you get to kind of express yourself more.

Yeah, yeah. I think of what the needs for the label, and you know, a nice, simple portrait could be an album cover. Direct and simple and just getting that stuff because you know they want to see it's Bruce Springsteen. Then I do a dance, that’s what I call it for myself. Which is when I move over to this side and I see what the light is doing from that angle, and I move over to that side. Next I might change to a wider lens and I pull way back and I show all the atmosphere. Then like I see an opportunity for a silhouette and I'm like, "Oh, look at that, silhouette.” Then I might notice that he's got that great bracelet on or some nice rings. I mean, it's Bruce Springsteen's hands. He's made all these legendary guitar licks. Whoever it might be. Whether it's Dave Grohl or Willie Nelson or something. There's a story in those hands.

At the end of the day, it's all storytelling, you know? And the story has to be told in details, and close-ups, and wides, to tell the whole story.

The results we get to see from a lot of these shoots feel very intimate and personal. You already mentioned a lot of this is about relationships and friendships that you have built over the years. How do you balance wanting to get beautiful, intimate photographs with it being a set with other people on it? Do you try to minimize the amount of people that are present, like assistants, light, stylists, that kind of stuff?

If they're necessary, I'm all for having people be on the periphery that are helping me distract the subject, you know? It's nice to have people around that are kind of part of the fun, part of the process. Subjects tend to gravitate towards certain people. It's awesome and normally they'll gravitate towards me, but they might gravitate towards the stylist and think, "Wow I really trust this person." They might be looking off the side of the set to the stylist and ask "Is this right? You think this is working?" And you catch them looking over and they kind of have this real, honest, concern or joy or something and I keep shooting for that. Those are the things that like, when someone laughs and you capture that. I'm always looking for the moment.

I always tell my people on set, "Don't just jump in to the set without asking me first, because I might be seeing something that is more important than turning the collar down." And I might like the collar up. This has got to be like an unspoken rule. Then I can turn to them and say, "Okay, you need to fix something?" They're like, "Yeah." And they go in and fix it.

I think it is a balance to just keeping people comfortable and keeping the set loose and the relationships are important.

Has this process changed for you at all, from when you first started out to now as a very established photographer?

Early in my career I was afraid to direct anybody, because I was just happy to be there in the same room. They all looked so epic to me. When you first meet these people you hold them in such high esteem, Bruce, or Patti Smith, or Stevie Nicks, or Tom Waits. I'd be afraid to do anything or just would think to myself, "Oh my gosh, it's Stevie Nicks and she just looks great. It doesn't matter where I go.”

As you realize they're, you know, just regular people and they need direction and they want direction. Quite frankly my direction can help make a better photograph. And then we're collaborating because they might say, "Oh, what if I did this? Or what if I went and stand in that light?" Eddie Vedder particularly is super creative. He's a great collaborator because he's like, "What if we ... " Or, "What about this spot. I really like this little corner. The light." And I'm all for it. I'll make a left turn any minute that my subject has an idea.

Tom Waits is a great collaborator because he shows up with a truckload full of weird props. That stuff just couldn't make me happier, you know?

Throughout that journey are their specific moments you remember where something changed for you?

There have definitely been stepping stones along the way in my career. One of the first ones was when I did a workshop in Yosemite and where Annie Leibovitz was one of the instructors. Getting to see her work was very interesting because at the time you kind of believe that it’s basically magic. Being able to be standing next to someone while they're making such beautiful images, and, seeing that it's actually a real human being taking real photographs was really eye opening for me.

I also was invited to be an intern at her studio and that was a huge turning point for me. Then, I would say sort of early to mid career, I was doing a short film with Bruce Springsteen for his Devils and Dust album. There's a photograph of mine of Bruce sitting in his farm house on his property with a guitar, and a harmonica rack on. And, I recall when I took the photograph that I was looking through my camera, and I thought to myself "I'll be damned. You know, here I am taking photographs, and I'm looking through this view finder and Bruce Springsteen is on the other side," you know? That was one of the moments for me that really stands out to me photographically.

A lot of the people that we've mentioned so far are essentially rockers. But you've also shot a lot of Hip Hop artists. Is there any difference at all in photographing from one genre to the next?

I don't think so. I feel like they're all artists and some people make you do all the work, and some people collaborate. I did the College Drop Out record for Kanye West and all those concepts, all the ideas were his. And it was really cool to show up and help him execute his vision.

In the early '90's, when I did the Nas Illmatic work and Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth, and a lot of Big L and O.C., Heavy D, a lot of these artists wanted it to be from their neighborhood. Nas’ Illmatic was about being from Queensbridge. That’s where he grew up and what these songs are about. To go there and document was incredible, because his whole neighborhood showed up. I really felt like a documentary photographer there. I was documenting this moment in history and nobody knew the guy was going to be huge. Nobody knew it was going to be one of the top Hip Hop records of all time, forever, and ever. I don't think it's going to change.

Do you remember that shoot, what that shoot was like? You show up and you're in Queensbridge, which I assume you may have not been there before, before that?

Right.

What was that process like? You step into Queensbridge and then what happens?

The cool thing that happened was that I photographed M.C. Serch, from 3rd Base, and he basically had discovered Nas. I'm sure he wouldn't take total credit and there were a handful of people who were a part of it, and their names are eluding me right now.

Faith Newman?

Faith, Faith, yeah. So Faith and that team had really felt strongly about it. So anyway, I knew Serch. I didn't know Faith well at the time, before I shot it, but he came to me and said, "Hey, I have this artist and you need to photograph him. I Like, your style. You're the guy. Here's the tape. His name is Nasty Nas.

So he gave me this tape, which I wish I still have to this day, because it'd probably be worth a pretty penny, certainly culturally. I took it into the darkroom as I had done many times. I forget if I was living in Jersey City or if I was living in New York City at the time, but I had a darkroom in both of those places.

I just listened to it and did my printing. I felt how cinematic the record was and how cool it was and I was excited to know that they wanted to go to their neighborhood to shoot. So when I showed up, it was the Queensboro Bridge projects and the Queensboro Bridge was right there. It was, to me, a visual dreamland to photograph this guy.

When we were there, all his friends showed up and were a part of it and were all hanging out. I just included them into it. I would pull back really wide and shoot him and his friends smoking a blunt under the bridge. Him walking down the street. Him sitting on a park bench in the projects with all of his crew. You know, gin and juice and the whole nine yards. It was really cool. The whole community embraced me because I was helping their guy, you know?

Afterwards I've brought those photos to Nas, because we continued to shoot together. It ended up that he was going through the list of people who were no longer alive, or who were in prison, or who were still alive. He was just like, "This guy's in prison. This guy's in prison. This guy's no longer around. This guy died. This guy's my brother, he's still around." It was crazy for someone like me who didn't grow up in the projects around a lot of drugs and gun violence, you know?

Recently I was doing a shoot with him at the O2 in London, and he just looked at me and he said, "Danny, look at us. Look at us two. Who would have thought after hanging out in Queensbridge that we would be shooting a billboard for Times Square in London?"

You know, like 20 years later? I was like, that's cool.

So cool. I know this is a long time ago, but do you remember what film stock you shot during that particular Illmatic shoot and on which camera?

Oh, yeah. I shot a lot of Tri-X. I shot my Hasselblad. I shot my Widelux. The classic shot of Nas walking through the streets and looking back over his shoulder is shot on the Widelux. The cover, for which the little kid photograph was taken by maybe his mom or his dad, but the background of it was one of my photographs that was taken on a Polaroid camera. So it's a 665 Polaroid. Then a lot of the color stuff was shot on Kodak Ektachrome EPT, cross-processed.

Do you have any idea how many rolls you shot for that first shoot that ended up creating the album packaging?

Oh, man. I bet I probably shot easily 30 rolls of film. Maybe even 50. Nobody's asked me that question before. It was a full day!

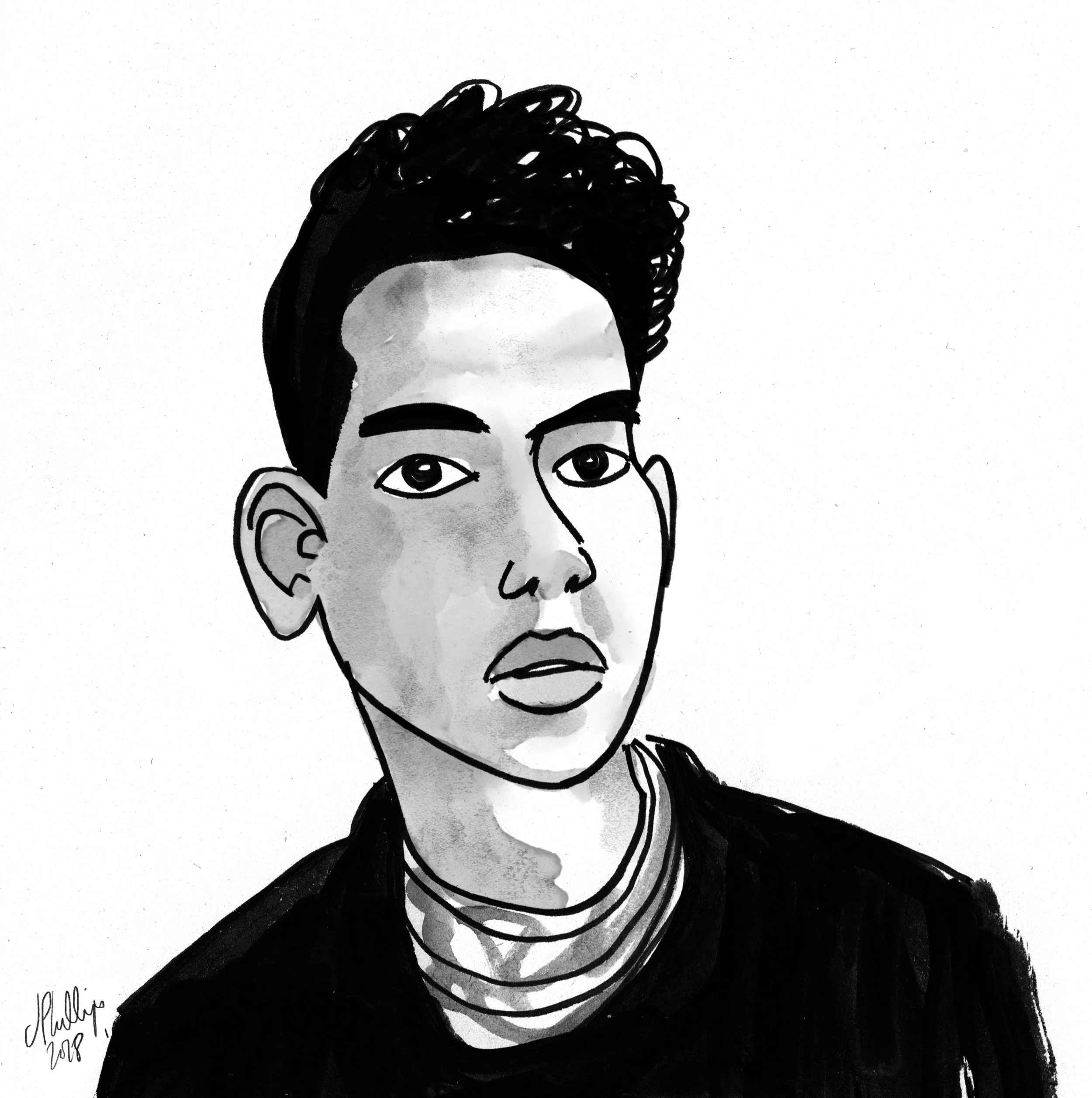

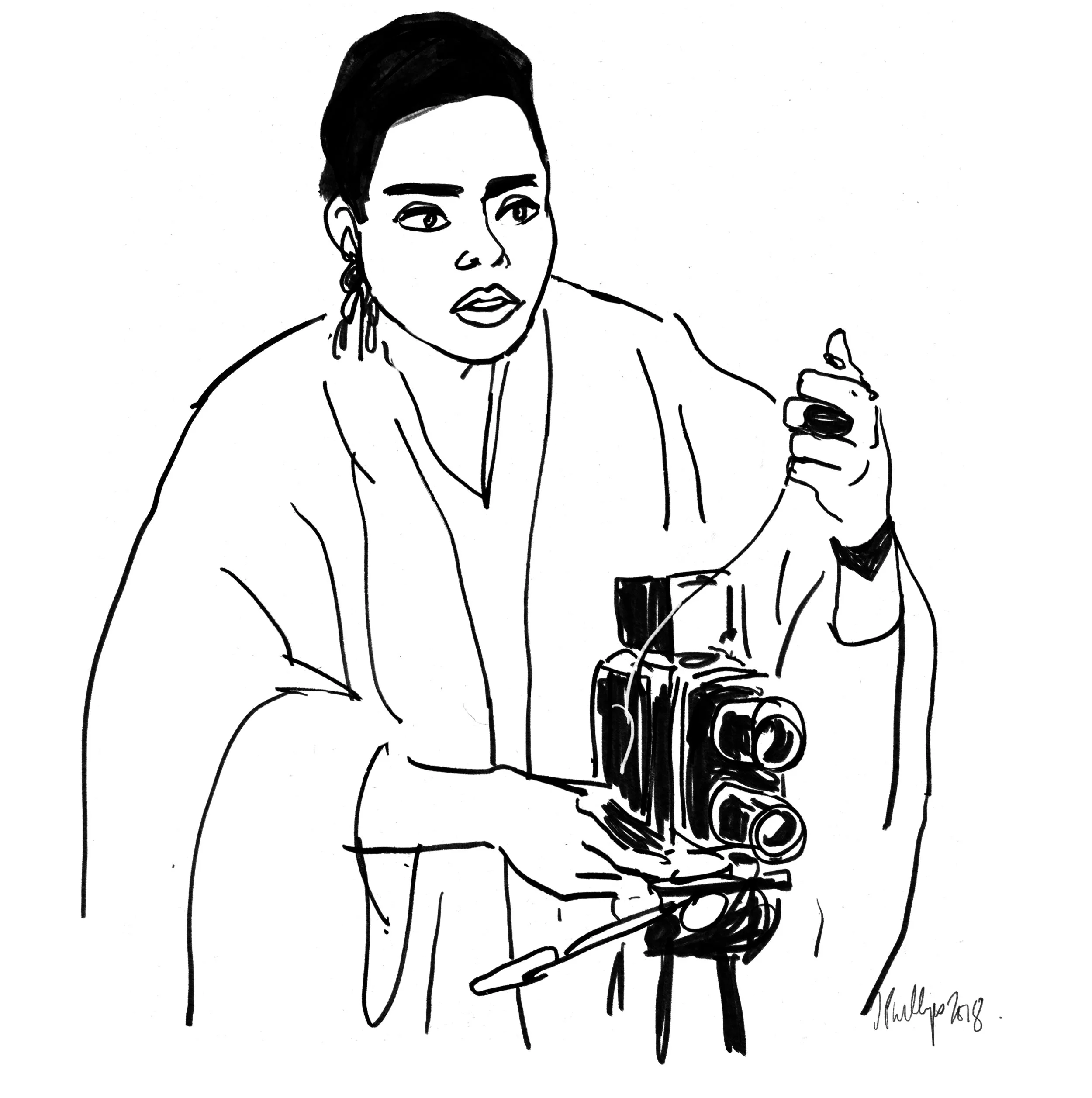

Photo Illustration Reference: Long Island Pulse Magazine